HJ: In the metaphysical community, we hear a lot about chakras and their effects and role in the body, often times with very little in the way of science to back up what is being said. Whether or not science is able to support a theory or concept is not the deciding factor in its legitimacy. Certainly science is unable to explain many things that are absolutely real and valid. And, of course, there is much validity to our subjective experience that is always real and significant in metaphysical terms. However, it is always interesting to have phenomenon like the chakras explained/explored on a scientific level, as it is just one more aspect through which we can understand their complex function in the body, thereby opening different avenues with which we can interact with them. For example, if we identify certain hormones or amino acids that are associated with a chakra, we can learn that we may be able to affect and potentially enhance their activity by consuming more of the said nutrient.

Therefore, we present to the Healers Journal community this in-depth three part series on the physiological basis of the chakras and how they interact with the mind-body-spirit triad. This is a very interesting and enlightening series of articles that receives our highest recommendation. Learn, grow, expand and enjoy.

– Truth

On a Possible Psychophysiology of the Yogic Chakra System (Part 1)

By Dr S.M. Roney-Dougal | Yoga Mag

—

Abstract

Recent theoretical research by myself into the pineal gland as the physical locus of ajna chakra, conceived in the yogic tradition as being the psychic centre of our being, is extended here to explore the yogic idea of ajna chakra as the command chakra, in command over all the other chakra centres. I have come across multiple references to the importance of melatonin as the off-switch for the endocrine glands’ output of hormones, working together with the pituitary gland, which is considered to be the on-switch. I am suggesting that the pineal gland is the physical aspect of ajna chakra; the thyroid of vishuddhi; the breasts of anahata; the adrenals of manipura; and the gonads of swadhisthana and mooladhara. These endocrine glands are all positioned at the traditional points of the chakras and their functions are remarkably equivalent to the traditional descriptions of the chakra functions. I am therefore proposing that the endocrine system is the physiological aspect of the yogic spiritual tradition of the chakras, and that the autonomic nervous system can be equated with the yogic nadis.

Over the last quarter of a century, there has been increasing interest in ‘translating’ the knowledge of one system into the language of another. For example, 20th century physicists have been comparing quantum mechanics with mystical knowledge as exemplified by Fritjof Capra in The Tao of Physics (1975). This same process has been occurring in psychology, for example Tart’s Transpersonal Psychologies (1975), Paranjpe’s Theoretical Psychology (1984), both examining Eastern philosophies and religions from a Western psychological standpoint, and research exploring a neurological basis for near-death experiences and their similarity with the kundalini experience (Wile, 1994; Jourdan, 1994).

Much of this translation has, of necessity, been in general terms, since we have to clarify the overall picture first. I seem to be involved in this process from a rather different perspective. I have been researching a specific topic, the pineal as a psi-conducive gland, which has generalized to the endocrine system as the physical aspect of the yogic chakra system. I must stress that what follows is still in a speculative and exploratory stage.

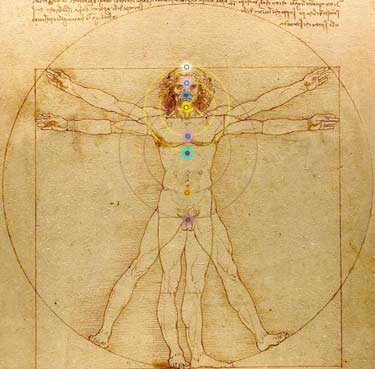

The yogic chakra system

The yogic chakra system as explained by Swami Satyananda Saraswati (1972b) consists of seven chakras which are normally depicted as a sort of ‘spinal column’ with three channels called nadis (ida, pingala and sushumna) which interweave, the crossing-points being the sites of the chakras (See Figure 1).

In Western terms this can be readily understood as the central nervous system (sushumna) in the spinal cord around which, on either side, runs the autonomic nervous system which has two aspects, the parasympathetic which can be readily correlated with ida, and the sympathetic with pingala, the sympathetic and pingala being the activating aspect of the system and the parasympathetic and ida the relaxing. Where these two cross they form plexuses, or nodes, from which nerves go out to, for example, the heart, lungs, diaphragm, digestive system and the endocrine organs. Satyananda connects this nervous system with the chakras as follows in Table 1.

These chakras are considered to be important points for the channelling of consciousness, energy nodes linking the physical with the spiritual. They have been adopted quite widely into popular usage in the West, partly through the Theosophists at the turn of the century, and partly because of the intense interest in Eastern spirituality birthed during the sixties. There are at present so many different correspondences and attributes linked to them and therefore this research is presented with the aim of achieving greater clarity.

The pineal gland: ajna chakra

As a parapsychologist I am interested in the Indian lore surrounding ajna chakra, which is held to be the psychic centre. This corresponds very closely with Western lore which considers the pineal gland to be the ‘third eye’ or ‘the seat of the soul’. Swami Satyananda (1972a) states that: “The name ajna comes from the root ‘to know’ and ‘to obey and to follow’. Literally the word ajna means ‘command’… Yogis, who are scientists of the subtle mind, have spoken of telepathy as a ‘siddhi’, a psychic power for thought communication and clairaudience, etc. The medium of such siddhis is ajna chakra, and its physical terminus is the pineal gland.” I consider that his concept of the pineal gland as the psychic chakra and as the command chakra has a sound psychoneuro-endocrinological basis.

The pineal gland is situated in the centre of the brain and its main function is to make neurohormones which affect both the brain and the body. The pineal works with the pituitary through the hypothalamus, controlling the endocrine system. Basically it is one of the regulators of our circadian rhythm, is implicated in our emotional state, reproductive function, possibly dream sleep and in certain psychoses. Melatonin is the best studied of the pineal neurohormones and was first isolated from cattle in 1963. Before this the pineal was generally considered in the West to be vestigial. Amphibians and reptiles have light sensitive cells in the pineal gland which, for them, is literally a light sensitive third eye at the top of their brain just below their skull. In humans, fibres from the inferior accessory optic tract go to the pineal; these are separate from the main optic tract bundle, which suggests that the light sensitivity of the pineal is not necessarily related to sight (Eichler, 1985).

Most people have heard of the pituitary gland, often known as the ‘master gland’ in that the hormones it makes exert a controlling effect on the endocrine organs. We can think of the pituitary as being an ‘on switch’ and the pineal as being an ‘off switch’ (the mistress gland) in that it works with the pituitary by switching off the endocrine organs. The form of ajna chakra is traditionally depicted as bilobed and we can understand this to be the joining of the two glands, pituitary and pineal, which makes very good sense from a neuroendocrinological point of view. To me this makes much better sense than assigning the pituitary to sahasrara, the crown chakra, as some systems do, since sahasrara is better understood as the culmination of everything, the whole rather than any of the parts. Just as mooladhara is considered by Satyananda to be the top chakra of animals and the bottom of humans, so sahasrara can be understood as the top chakra of humanity and the bottom chakra of the next order of being, whatever that may be.

The psychic chakra: pinoline

There is a large body of neurochemical and anthropological evidence which suggests that the pineal gland may produce a neuro-modulator that enhances a psi-conducive state of consciousness. An abstract of this research was presented at the Parapsychological Association Convention in 1985 (Roney-Dougal, 1986). For full details of this research please see Roney-Dougal (1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1993). In brief, the pineal gland has been found to synthesize various beta-carbolines and peptides, and to contain enzymes that produce psycho-active compounds such as 5-methoxy dimethyltryptamine (5MeODMT). “The two precursors that are most likely to be involved in the synthesis of such compounds are serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5HT) and tryptamine” (Strassman, 1990). These have wide-ranging effects throughout our brain and body, affecting the gonads, adrenals, pancreas, thyroid, and other emotional and endocrine activities.

Of most interest here are the neuromodulators called beta-carbolines which are MAO inhibitors that prevent the breakdown of serotonin. This results in an accumulation of physiologically active amines within the neuronal synapses which may lead to hallucinations, depression or mania depending on the amines being affected (Strassman, 1990). Beta-carbolines are also found in the retina of the eyes, in the adrenal glands and in the gut. The pineal contains the greatest concentration of serotonin in the brain, this being accentuated in those who suffer from psychoses. The pineal also contains enzymes that inhibit synthesis of these compounds, thus suggesting a regulating mechanism within this gland. There is a suggestion that it is the action of the pineal beta-carbolines, in particular 6-Methoxytetrahydrobetacarboline (6MeOTHBC, now being called pinoline), on serotonin that triggers dreaming (Callaway, 1988). Spontaneous case collection studies (e.g. Rhine, 1969) have found that many spontaneous psi experiences occur during the sleeping and dreaming state of consciousness, which suggests that dreaming is a state of consciousness whereby we are likely to have psi experiences. This has been confirmed experimentally (Ullman, Krippner & Vaughan, 1973). Pinoline is suggested to be the neurochemical that triggers this particular state of consciousness.

Anthropological data also suggest that these beta-carbolines are psi-conducive because their chemical structure is very similar to a naturally occurring group of chemicals called harmala alkaloids which occur in an Amazonian vine, Banisteriopsis caapi, used by Amazonian tribes for psychic purposes (Roney-Dougal, 1986 & 1989) (See Figure 2). The Amazon has a huge variety of psychotropic plants, yet all the tribes throughout that vast area use this same vine mixed with Psychotria viridis (Nai kawa) which contains dimethyltryptamine (DMT) (Ott, 1993 & 1994), for healing, out-of-body experiences, clairvoyance and precognition. It is traditionally used only when psi experiences are desired, though nowadays it is also used for general initiatory purposes. Thus the tribal people make a mixture of harmala alkaloids and DMT which mimics the tryptamine-pinoline mixture ascribed to the night time output of the pineal gland. My speculation is that when the pineal gland is stimulated to produce pinoline we are more likely to enter an altered state of consciousness which is psi-conducive.

In the 1960s a Chilean psychotherapist, Claudio Naranjo (1973, 1978) used a variety of hallucinogens including harmaline (one of the harmala alkaloids) in the psychotherapeutic setting, and came to the conclusion that: “Harmaline may be said to be more hallucinogenic than mescaline. . .both in terms of the number of images reported and their realistic quality. In fact some subjects felt that certain scenes which they saw had really happened and that they had been as disembodied witnesses of them in a different time and space. This matches the experience of South American shamans.” (Naranjo, 1967). Ott (1993) considers that the harmala alkaloids are not actually hallucinogenic in their own right, but that they permit the DMT in the ayahuasca mixture to be absorbed into the blood stream so that these create the entheogenic effects. This is still a matter of debate. There is extensive evidence from many anthropologists which suggests that the Banisteriopsis vine together with Psychotria Viridis is a psi-conducive drug, particularly with regard to remote viewing, clairvoyance and precognition but so far there has been no experimental test of these claims (Kensinger, 1973). Ayahuasca has recently been investigated by Don et al (1996) who suggested that its action is consistent with their other research into brain function and psi experience.

Thus, the anthropological evidence suggests that harmala alkaloids mixed with DMT stimulate a psi-conducive state of consciousness; the neurochemical evidence suggests that the harmala alkaloids are an analogue of pinoline which is produced in the pineal gland, noting that in the comparison between the action of the harmala alkaloids and pinoline it must be remembered that a one-position change in methoxy grouping can be profound in its action. The yogic and occult teachings and common folk lore all say that the pineal gland is the psychic centre and I suggest that the pinoline made by the pineal gland at night time, through its action on seratonin, stimulates a dream type state of consciousness which is psi-conducive.

The command chakra: melatonin

However, the yogic lore not only equates ajna chakra with the psychic centre of our being, but also as the command chakra. For an understanding of the pineal gland as command chakra we have to look to its main action which is the production of the neurohormone melatonin. Melatonin is found in protozoans, suggesting that it dates back a thousand million years, and is found in all animals. It is important in bird migration cycles, dogs’ moult cycles, and frog colour change. In this article I refer both to research with humans and with animals in order to obtain as full a picture as possible of the relationship between the pineal gland and the endocrine organs since there has been relatively little research with humans, whilst being very aware that one should not extrapolate too much from animal data as is the tendency so often these days in biological and psychological research. Therefore, as far as possible, whenever the data comes from animal studies I state this explicitly.

The most important function of the pineal gland is maintaining the biological clock, both on a daily basis according to the sun, on an annual basis according to length of day, and on a lunar basis as well. The study of the biological rhythm is called chronobiology and it has been found that there is a genetic connection, a basic inner clock, and an environmental connection through the retina: light stimulates the monosynaptic retinohypothalamic pathway which leads directly to the anterior hypothalamic suprachiasmic nucleus (SCN), pineal and hypothalamus.

Within the pineal, the circadian rhythm regulation is achieved through the actions of serotonin and melatonin. Serotonin is made during the day and melatonin at night. Acute exposure to light at night suppresses melatonin production. The intensity of light required to suppress production varies between species and in humans is 2000 lux. It has been suggested that perhaps rhodopsin is the photopigment that mediates the suppressive effect of light on pineal. Blue light seems to be maximally inhibitory (500–520 nm). Acute exposure to nonvisible, non-ionizing radiation, e.g. extra low frequency (ELF) 60 Hz electric and magnetic fields also suppresses melatonin production as does pulsed static magnetic field exposure. There is speculation that these effects are also mediated via the eyes (Wetterberg, 1995, Reiter & Richardson, 1992).

Seratonin is a very important neurotransmitter in the brain and its action has been linked with mental states such as psychosis, with entheogenic plants, with our mood circuits and therefore with illnesses such as appetite disorders (anorexia and bulimia). It is a very complex neurotransmitter with 5 or 6 different receptor sites, which means it has many different modes of action.

Melatonin is made from serotonin through the action of two enzymes, serotonin n-acetyl transferase (NAT) and hydroxy-indole-O-methyltransferase (HIOMT). Melatonin production is determined primarily by neural activity from the hypothalamic suprachiasmic nucleus (SCN) and there is a feedback relationship with the endocrine glands. Gonadal steroids, pituitary gonadotrophins, thyroxine, prolactin and the adrenal hormones intervene in the mechanisms governing melatonin synthesis.

All humans have a circadian rhythm though the magnitude of NAT production varies greatly. In general there is good correlation between pineal NAT activity and pineal and plasma melatonin rhythms. The rhythm at birth is linked to that of the mother; maturation of the cycle accompanies growth of sympathetic nerve fibres into the gland; melatonin production peaks just prior to puberty when there is a sudden and dramatic drop, and from then on it gradually decreases into old age.

The most important neuronal function of melatonin is as a sleep inducer. It has been found to ease insomnia because it causes drowsiness, and also to combat jet lag because it helps to reset the biological clock: 5mgs per day helps induce sleep and helps airline workers adjust to new time zones. (Cowley, 1995). Is there a genetic component in early or late risers? Hypophysectomy (loss of the pituitary gland), which causes depressed metabolic activity, and bilateral adrenalectomy blunt the nocturnal melatonin rise though the rhythm stays the same.

Being forced to exercise (swim) at night causes a rapid drop in pineal melatonin levels in rats, but not in NAT or HIOMT activity. Melatonin production stays as normal, and blood levels rise dramatically suggesting it is being rapidly released from the gland into the blood system. Removal of adrenals doesn’t change this so normal stress hormones are not implicated. This finding has profound implications for the health of night workers (Reiter & Richardson, 1992) because melatonin also modulates release of stress hormones, thereby controlling heart attacks and stomach ulcers.

Jogging or other exercise is a mood enhancer since it stimulates endorphins. Exogenous opiates increase melatonin levels, and beta-endorphin levels decrease when melatonin is administered. Opiates stimulate basal prolactin secretion. Opioid receptor antagonists also decrease prolactin concentrations although continuous administration does not affect circadian rhythm of prolactin, which is related to melatonin levels.

Recent research suggests that melatonin is involved in the ageing process and that giving 19 month old mice melatonin each evening in their water improved their weight, their vigour, their activity levels and their posture when compared with the untreated mice and they lived almost 200 days longer on average (20%) (Maestroni et al, 1989). Touitou et al (1989) measured melatonin levels in people in February, March and June and found that old people have half the amount of melatonin that young men do (we make half as much by age 45 as we do when children), that senile people show far less circadian rhythm, with elderly women showing least variation. For all groups, all through the year melatonin production peaks between 2–3 a.m. with the largest amplitude in January. Inter-individual variations are large in all groups. Since pinealocytes and enzyme activity are not altered in the pineal of the elderly, the decline of plasma melatonin levels may well be related to a modification in the release of the hormone and/or to an increase in its metabolism or excretion. An increased sensitivity to light could also explain the relatively low levels of plasma melatonin in the elderly.

Melatonin production decreases as we age, the thymus gland shrinks and we produce fewer antibodies and T-cells. There are special melatonin receptors on cells and glands of the immune system. A recent controversial speculation is that nightly melatonin supplement boosts the immune system thereby preventing cancer and extending life. Research has suggested that melatonin protects cells from oxidation by free radicals, which contribute to at least 60 degenerative diseases, including cancer, heart disease, cataract and Alzheimers. In this respect melatonin differs from other natural antioxidants, B-carotene, vitamin E and vitamin D in that melatonin is absorbed into target cells and exerts its action from that intracellular position with much greater effect (Reiter, 1995). Melatonin reduction is linked to the calcification process that starts at puberty. People taking chlorpromazine, an anti-psychotic medication that raises melatonin and prolactin levels have low rates of breast cancer. Prolonged exposure to high oestrogen levels raises breast cancer levels and melatonin inhibits oestrogen release.

It thereby also helps to prevent pregnancy because of its interaction with the reproductive system as a hormone inhibitor. This inhibitory action means that melatonin controls puberty; without it we would be sexually active at 4–5 years old. Parapineal tumours, those that lie next to the pineal, stop the pineal from functioning and lead to precocious puberty and progeria (accelerate ageing); while pinealomas, tumors of the pineal gland itself, produce excess melatonin secretion and delayed puberty.

Thus melatonin functions to affect the body in ways which are traditionally connected with yogis: yogis are said to live for many years longer than normal; are considered to be relaxed and stress-free people; to be able to control many of their physical functions, such as heart rate, circadian rhythm and metabolic rate; celibacy is linked to the religious life, and within yoga there is also the tantric path; and they are considered to enjoy excellent health.

Through the light sensitivity of the pineal gland and its primary role within the biological clock system, regulating the rise and fall of the metabolic system and switching off the endocrine glands, which I am going to expand on next, we can see that there are considerable grounds for the concept of the pineal as the command chakra.

1 First published in the Journal of Indian Psychology, July 1999, Vol. 17, No. 2.

Reprinted with the permission of the author, S.M. Roney-Dougal, Psi Research Centre, Glastonbury, Somerset, Britain.