HJ: Creativity, insight and inspiration are the products of habit, not chance or luck. Like sowing seeds in a garden, you must plant the seeds of creative inspiration in your life and particularly in your brain. And furthermore these can be planted by adopting certain mindsets and ways of viewing the world and approaching life. In fact, there is an entire science of modeling these traits from the worlds most successful and/or creative people — it’s called Neuro Linguistic Programming (or NLP for short) and it is very powerful.

Either way you go about it, the article below is a quick, powerful primer on how to train you brain to quickly get in touch with your creativity, insight and inspiration and make it an integral and effortless part of your day to day life.

– Truth

Insightful Thinking: How to Do It

You can learn how to be more creative.

By William R. Klemm, D.V.M, Ph.D. | Psychology Today

—

Genius is defined by creativity. Albert Einstein is often regarded as the epitome of genius. Nobody seems to understand his genius other than to say that it bubbled up like uncorked champagne. But the story of his work paints a different picture. His discovery of Special Relativity, for example, came as a stepwise series of small insights spread over many years of incubation.

Einstein used systematic ways of thinking to unleash his creativity. His success was not magic. There was method to his genius. First, Einstein relied heavily on thinking with visual images rather than words. Many famous scientists claim that their best thinking occurs in the form of visual images, even at the level of fantasy. Words and language, according to Einstein, had no role in his creative thought and math was used mainly to express the ideas quantitatively. Einstein, for example, in one of hisfantasies visualized himself riding on a beam of light, holding a mirror in front of him. Since the light and the mirror were traveling at the same speed in the same direction, and since the mirror was a little ahead of the light’s front, the light could never catch up to the mirror to reflect an image. Thus Einstein could not see himself. Another example of his use of imagery is his thought experiments visualizing train movements. Although fantasy, such thinking is not the product of a hallucinating mind; there is clear logic and order embedded in the fantasy.

A second reason for Einstein’s creativity is that he was unafraid, even as an unimpressive student and a patent clerk without recognition as a scientist, to challenge no less an authority than James Clerk Maxwell when the thought experiment could not be explained by current electrodynamic dogma.

Third, Einstein thought long and hard on this problem for over seven years when he published his seminal paper in1905 at the age of 25. Actually, he said in his autobiography that he started pondering the problem when he was 16. The point is that the revelation did not happen in an instant—it was the product of incubation. Actually, his ideas were fermenting for years, where he repeatedly thought about alternative possibilities and eliminated those that didn’t add up. By the process of elimination incubated over a long time of thinking, the final solution became accessible.

This view of creativity is consistent with the view of Linus Pauling, who won two Nobel Prizes and came within a hair of decoding DNA structure that would have won him a third. He said, “To have a good idea, you have to have lots of ideas.” All exceptional scientists generate lots of ideas, and then winnow out the ones that are practical for testing by experiment. In other words, Einstein and Pauling are proof that creativity is not as inaccessible for ordinary people as it seems. There are systematic ways for everyone to become more creative.

These ways of thinking can be taught and used by anyone. Young scientists aspire to have an early experience of working for a time in the lab of a famous scientist, in the hope of learning how to make discoveries. Many Nobel Prize winners have been students of other Nobel Prize winners. Consider the case of Hans Krebs, who discovered the energy-production process in cells. His “family tree” of scientists shows the following relationships of science teachers and mentors:

Berthollet (1748-1822)

Gay-Lussac (1778-1850)

Liebig (1803-1873)

Kekule (1829-1896)

von Baeyer (1835-1917)

Fischer (1852-1919)

Warburg (1883-1970)

Krebs (1900- 1981)

All of these men were famous and each of the last four received Nobel Prizes, which began in 1901. A role model for Hans was Otto Myeroff, who worked in the same institute and who received the Nobel Prize in 1922. This tree is cultural, not biological. There was only one scientist in Hans’ biological family tree, a distant cousin, who was a physical chemist.

In the years (1926-1930) Hans studied with Otto Warburg, where he learned the value of inventing new tools and techniques for conducting experiments to test ideas about energy transformation in living tissue. Another important lesson was the value of hard work on ideas. Warburg worked long and hard hours all his life; he was working in his lab eight days before he died, at the age of 81.

* * *

Creativity is a subset of a general learning competency that entails correct analysis, understanding, insight, and remembering. Here, I stress the importance of insight, often referred to as “thinking outside the box.” Moreover, I make the claim that this competency can be taught and mastered through practice.

This mode of thinking goes by other names, such as lateral thinking or “thinking outside the box.” Whatever you call it, such thinking requires breaking the constraints of predispositions, limiting assumptions, bias, mental habit, and rigid past learning.

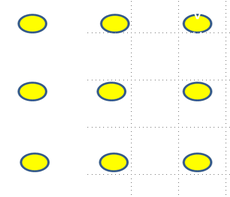

See if you can solve the problem below, which is a simple illustration of the common problem of self-imposed limitation of thinking:

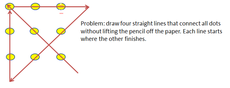

Problem: draw four straight lines that connect all dots without lifting the pencil off the paper. Each line starts where the other finishes. Can you do it?

In case you didn’t figure it out, here is one solution:

Many people can’t do this task. Reasons for failure here and with other creativity challenges include:

- Improper understanding of the problem. Failure to recognize what is allowed and what is not.

- Failure to look beyond the ideas that first emerge.

- Being so close to a solution that you keep working with the same flawed approach.

Frame the Issue Properly

The sample dot-connection task above illustrates the problems you get into by the way you have framed the problem. When faced with any problem, it is natural to make certain assumptions about facets of the problem that were not explicitly stated. In the above, case, I didn’t say that the lines had to stay within the borders of the dots, but many of you probably made that assumption. You were actually free to make the assumption that it was o.k. to do that.

The way we classify things creates a logjam to new ideas. For example, something in Newton’s sensory or cognitive world caused him to see the similarity between an apple and the moon in a new way; of course they were both round, solid bodies. But it is not clear what caused him to perceive what is now obvious, namely that both are subject to the effect of gravity. Even seeing the apple fall from a tree would not be a meaningful mental cue for explaining moon motion to most people, because they are not used to thinking of the moon as “falling.” Creative thought is affected by the ways in which we classify things. We put apples and moons into categories; but by insisting on describing and naming them, we restrict the categories to which they belong. Apples are supposed to be round, red, and sweet, while moons are large, yellow, rocky, and far away. The names themselves get in the way of thinking of either as a classless object that is subject to gravity. A lesser order of creativity is commonly seen in the simple realization of the significance of obvious associations. The associations may even be negative (e.g., if penicillin is present on a bacteriological plate, the organisms will NOT grow).

A question calls for an answer: a problem, its solution. The trick is not only to ask questions, but to ask questions or pose problems in the most effective ways. A question can easily limit creative thinking if it restricts the space of potential answers. It therefore is important to pose questions in open-ended ways and ways that do not make too many assumptions about an acceptable answer. A major part of the creativity task is proper formulation of the problem itself.

Improving Creative Thinking Ability

People who have looked carefully at the creative process have learned that everyone of ordinary intelligence has latent creative abilities that can be enhanced by training and by a favorable environment. But many of us have not developed our creative capacity. Our brains seem frozen in cognitive catalepsy, boxed in by rigid thinking.

One book that is dedicated to improving creativity is by D. N. Perkins, The Mind’s Best Work. He finds that after-the-fact anecdotes about well-known examples of great leaps of creative thought have generally received little or no close scrutiny of the mental processes that led to them. There are too many opportunities for the real mental correlates of creativity to be lost through excitement and distraction (as part of the “eureka” phenomenon), lack of need or desire to reconstruct the thought processes, and faulty skill and memory in reconstructing the process. Experiments where people have been asked to think aloud or report their thoughts during an episode of invention led Perkins to conclude that creativity arises naturally and comprehensibly from certain everyday abilities of perception, understanding, logic, memory, and thinking style.

Generating Insight

As an indication that creativity can be taught and learned, I offer the following personal anecdote.

“Grade = C. Klemm: Your work shows a lot of industriousness. Strive for INSIGHT!”

That note was scrawled across an assignment paper I had turned in to my professor, C. S. Bachofer, at Notre Dame. I had worked very hard on that paper, was quite proud of it, and had expected an A. Decades years later, I could still see that message, seared into my memory like a brand on cow hide. It was as if he meant that I was not smart enough. If true, how was I supposed to make myself smarter? Isn’t that a born capacity? You either have it or you don’t.

As the years went by, and I became a professor myself, I gradually came to realize that Professor Bachofer was really saying something else. He was telling me to discover in my own terms and learning style the tactics and techniques that can develop insight capability. I now know that it IS possible to learn how to become more insightful. Some of this may be teachable to others.

Idea generation has little to do with intelligence. I remember a graduate student of mine at Iowa State University who had great test scores and allAs from six years of college work. As was my practice, I tried helping this student develop a thesis project by giving him a published research paper and asking him what ideas occurred to him? After the first paper, he said nothing particular came to mind other than what was reported in the paper. So, figuring I had just picked a paper that was too mundane, I gave him another paper. Again, the same result occurred. After about four or five tries with the same result, I said, “I’m afraid this is not going to work. You really should not go into this line of work. In any case, if you persist in this ill-advised quest, you will have to find another major professor.”

So how could this student have generated ideas? First, he should have been looking for alternatives. In reading, for example, I focus on what the author did not say. This not only stimulates me to think of other possibilities but also improves my ability to remember what was written. Thinking about something is the best way to rehearse the memory of it.

Thinking of alternatives requires imagination. Young children have lots of imagination. Unfortunately, school tends to stamp that out in the first few years. This is one reason I like to use mnemonic devices to promote memory. All these devices require imagination, and the more you exercise this capability, the better you can get at it.

Idea generation needs to be valued. School tends to devalue creativity. Expectations are to learn what is dished out and pass a high-stakes test on it. What educators value most is understanding and remembering accepted knowledge. Do we believe students are too dumb for higher level thinking? Do we believe that these higher skills are innate and cannot be taught? Do we believe that maybe they could be taught if we only knew how?

The Creative Process

The literature on the creative process is vast, and I can only summarize it here. Have you seen the advertisement from IBM Corporation, in which there was a long alphabetized list of “old English” words? The ad’s caption read, “Anyone could have used these 4,178 words. In the hands of William Shakespeare, they became King Lear.” King Lear epitomizes the essence of creativity: to take commonly used and understood ideas and recombine them in elegant new ways.

Some practical advice on how to think innovatively is provided by Beth Comstock, the CMO at General Electric. She was inspired by a brilliant boss who wasn’t afraid to offer an idea before its time. Even though many of his ideas were absurd, many were also gems. None of these would have been born had he not been willing to “put it out there.” As Einstein said, “If at first the idea is not absurd, there is no hope for it.” The point is that creative ideas often come of the oven half-baked. Typically, the recipe has to be modified.

Comstock’s advice includes:

1. Nurture the newborn idea. Absurd ideas are all too easy to dismiss. Be patient with them and protect them from early-stage critical analysis. This accepting attitude lies at the heart of effective brainstorming. Get the ideas out on the table. They often will grow or transform into better ideas. Sit on them. Let them incubate.

2. Commit to a promising idea. Successful ideas are nurtured by passion. If you believe in the promise of an idea, noodle it to fit a meaningful problem. Do your homework. Smooth the rough patches. Ask others to help make the idea better.

3. Tell others, even when you feel embarrassed about how flakey the idea might be. This clarifies your own thinking and at least a few of your listeners may get intrigued and help you improve the idea.

4. Hang in there. Don’t be intimidated by negative feedback. Use such feedback to improve the idea. If necessary, put the idea in storage until improvements come to mind, or new technology or resources become available or others people are more accepting. If you believe in your idea, don’t give up.

A fundamental aspect of creative thinking is to be flexible in interpreting what you see or hear. Powers of observation include of course the ability to notice things. But just registering a visual or thought input is not enough. Creative brains see what others only look at. That is, creative brains look for implications.

A basic condition for a creative act is to combine known elements into new combinations or perspectives that have never before been considered. Perkins writes of the utility of deliberately searching for many alternatives so that many combinations and perspectives can be considered. Creativity is much more likely to emerge when a person considers many options and invests the time and effort to keep searching rather than settling for mediocre solutions.

The first and fundamental step in the creative process is to have a clear notion of what the problem is and to be able to frame it appropriately. Recall in the opening example how you framed the dot problem determined whether or not you could solve it. The effective thinker begins by first focusing on the structure of the problem rather than its technical detail.

Creative operations require conceiving alternative solutions. These come from each person’s permanent memory store, his or her lifetime data base of knowledge and experience. Memorizing does not impair thinking ― it can empower thinking. Other potential alternatives are brought in from such external sources of input as reading, ideas from colleagues, data bases, and other sources. Next, these alternatives can be processed logically (by associating, sorting, and aligning into new or unusual categories and contexts) or more powerfully by the use of images, abstractions, models, metaphors and analogies.

Thus, knowledge is not the enemy of creativity. One’s capacity for creativity depends on the store of knowledge. Einstein, for example, would not have discovered relativity if he had not known basic physics in general and Maxwell’s ideas and equations in particular. As my friend, Ann Kellet has said, “To think outside the box, you have to know what is inside the box.” The trick is to take a fresh look at what is inside the box.

The next stages involve noticing clues and potential leads, realizing permutations of alternatives that are significant, and finally selecting those thoughts that lead to a new idea. There are dozens of thinking tools that stimulate idea. Check out these tools at the Web sites ideaconnection.com, mindtools.com, and myucoted.com.

The process of considering and choosing among alternative approaches involves a progressive narrowing of options in the early stages of creation and a readiness to revise and reconsider earlier decisions in the later stages. Einstein ran into several blind alleys in his discovery journey. This narrowing process requires the creator to break down and reformulate the categories and relationships of thoughts and facts that are commonly applied to the problems and its usual solutions. The creative thinker examines all reasonable alternatives, including many which at first may not seem “reasonable.” Each alternative needs to be examined, not only in isolation, but in relation to other alternatives—and in relation to the initial problem expressed in different ways. The practical problem then becomes one of reducing the size of the problem and alternative solution space to workable dimensions. That may well be why one has to be immersed in the problem for long periods, with subconscious “incubation” operating to help sort through various alternatives and combinations thereof.

Note that all of these operations must occur in the working memory, which unfortunately has very limited capacity. That is probably the reason why insight and creativity are so hard to come by. Researchers of the subject of creativity would do well to look for ways to create more capacity for our working memory and to make it more efficient. The most manipulatible factor would seem to be the mechanics of supplying information input from external sources.

The final stages of creativity are more straightforward. They involve critical and logical analysis, which typically forces a refinement of the emerging ideas. Analysis should force the refinement of premature ideas and re-initiation of the search and selection processes. Sometimes, analysis will force the realization that the wrong problem is being worked or that it needs to be reformulated.

If you have but one wish, let it be for an idea

― Percy Sutton –

vikram

November 16, 2014

Wonderful article, thanks 🙂